BrainInfo BrainInfo

- Can there possibly be enough people hooked on the brain to account for 5,500 hits a day at a website called “BrainInfo”? Apparently so; this has been the pace since the site, hosted by the Washington NPRC, came on line March 1, 2001. Visitors hail from as close as next door and as far away as France, Brazil, Russia and Vietnam. About 40% say the reason for their visit is research, 40% are studying or teaching neuroanatomy, some 5% have a clinical interest, and 15% say they are just curious.

BrainInfo is the brainchild, so to speak, of Dr. Douglas Bowden, head of the Center’s Biostructure Technology Laboratory. The website represents a quantum leap in the ability of researchers to obtain and communicate information about the primate brain. To appreciate the magnitude of this development, consider that the brain contains about 500 primary structures, such as the hippocampus or superior colliculus, and that these structures and their groupings have more than 6000 names. Previously, researchers had to consult a number of textbooks and brain atlases and wade through a Babel of nomenclature to identify the area they were studying. Now, they can log onto BrainInfo and be in business with a few clicks of the mouse.

- For example, an investigator who is curious about a region that took up a particular stain can click to find the map most similar to

the affected cross-section, click on the area of interest to obtain a the affected cross-section, click on the area of interest to obtain a

- standard English name for it, and click again to learn all the other names it has been called. Another click produces other pictures of the structure in monkeys and in humans. If BrainInfo does not have a picture, it can send the visitor to other websites to view the structure: to the “Virtual Hospital” at the University of Iowa to inspect the area in dissected brain, to the UW’s “Digital Anatomist” in the Department of Biological Structure to view the same structure in human cross-section, to the “Whole Brain Atlas” at Harvard to see it in an MRI, or to UCLA to see a movie of it rotating in space.

- If the user wishes to know what has been written about, say, the hippocampus, BrainInfo can submit a query to the National Library of Medicine (NLM) website. The query will contain all of the names for the hippocampus, including “Ammon’s horn” and “Cornu ammonis,” so that the user does not have to key in a separate query with each different name to avoid missing important articles. This can be a considerable advantage, as the average structure has about six different names.

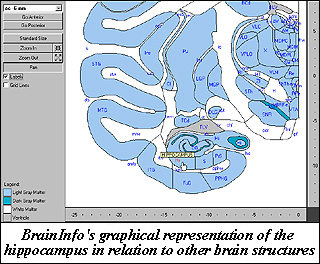

BrainInfo provides useful tools not only for neurologists seeking to unravel puzzles such as autism, parkinsonism and mental retardation,  but also for medical geneticists seeking to locate the genes responsible for such conditions. Its tools include a computerized “Template Atlas,” a set of some 60 drawings of cross-sections of the brain showing the boundaries of the primary structures displayed in each section. A page from the Template Atlas is like a city map showing hundreds of blocks in their various shapes and sizes. In fact, the BrainInfo website uses the same Geographic Information Software used by city planners and commercial developers. Just as a city engineer can overlay maps of, say, a local black-out with maps of electrical service areas to determine where the problem is located, a researcher can overlay a map of his or her findings on a stack of sheets to obtain information collected by other scientists about the same region of the brain. Scientists can also use the Template Atlas in conjunction with image-processing programs (e.g., Adobe Illustrator) to illustrate their own data for publication. In another useful application, they can fit Atlas drawings onto MRIs to show the location of structures not visible in the MRI. but also for medical geneticists seeking to locate the genes responsible for such conditions. Its tools include a computerized “Template Atlas,” a set of some 60 drawings of cross-sections of the brain showing the boundaries of the primary structures displayed in each section. A page from the Template Atlas is like a city map showing hundreds of blocks in their various shapes and sizes. In fact, the BrainInfo website uses the same Geographic Information Software used by city planners and commercial developers. Just as a city engineer can overlay maps of, say, a local black-out with maps of electrical service areas to determine where the problem is located, a researcher can overlay a map of his or her findings on a stack of sheets to obtain information collected by other scientists about the same region of the brain. Scientists can also use the Template Atlas in conjunction with image-processing programs (e.g., Adobe Illustrator) to illustrate their own data for publication. In another useful application, they can fit Atlas drawings onto MRIs to show the location of structures not visible in the MRI.

The impetus for BrainInfo came from a study in which Dr. Bowden recorded from some 3000 brain sites but then, when he consulted the literature, discovered that not one of the several hundred nerve tracts known to exist in the monkey brain had been illustrated sufficiently to permit a systematic analysis of his data. Resolving to remedy the situation, not only for his own research but for the benefit of all who study the primate brain, he submitted a grant request to NIH in 1977. The proposal was to develop an Atlas Data Management System on an IMSAI computer, which was state of the art at the time but was pre-Apple, pre-Microsoft and definitely pre-Web. “The NIH reviewers rejected what they regarded as a sci-fi fantasy,” he recalls. “They noted as gently as possible that they didn’t think the project was feasible on an 8K machine.” (In its current, still-embryonic incarnation, BrainInfo demands more than 20,000 times that kind of computer capacity!)

Despite skepticism at NIH, the concept of a computerized atlas of the monkey brain refused to go away. B. Atkinson, a computer-savvy graduate student who had contributed to the idea in his years at the Primate Center, took a job with the newly founded Apple Corporation and headed up a team that developed a Web-like software system that could store, edit and update both text and image information. This system, called HyperCard, proved perfectly suited for organizing the huge number of names necessary for the dictionary portion of the brain atlas system. Using HyperCard, Dr. Martin began in 1985 to assist with the development of NeuroNames, a database of 6,000-plus names that authors have used for the brain structures they study. At the same time, Drs. Martin and Bowden began work on the Template Atlas, using Adobe Illustrator to draw the many cross-sections revealing the primary structures of the brain.

The NLM made NeuroNames a source vocabulary of its Unified Medical Language System in 1993 and, in 1996, provided a grant to support the development of a brain information website. In 1997 the first version of the Template Atlas was printed and distributed through the Primate Information Center. That same year, Dr. Joan Robertson established BrainInfo’s predecessor website. Last year, Elsevier Science Press republished the Template Atlas drawings along with photographs of the original brain sections. Elsevier also produced a computer CD containing versions of the templates that scientists can load into their computers to map data derived from their own studies. Finally, on March 1, 2001, the BrainInfo website opened for business.

The advent of the World Wide Web in the mid-1990s expanded the concept of the project from a comprehensive brain dictionary and atlas, which could be distributed to scientists on a CD-ROM, into that of a “portal” through which users could gain immediate access to highly specific information about any part of the brain. The BrainInfo site is far from complete, but at 20,819 hits per day, it is clearly on its way.

|

|

|